Usable Security and Privacy #

This post provides an overview of the relevance of usable security. I address two questions: what is usable security? And how is usable security relevant for practitioners?

I am very passionate about human computer interaction (HCI) and cybersecurity. Thus, I decided to write this blog on a topic which is often overlooked by the cybersecurity community.

What is Usable Security? #

In a few words, usable security is the intersection of human computer interaction and cybersecurity. Usability, the human aspect, is often neglected when security products are developed.

What is this usability aspect in software? Literature mostly agrees on usability as the: effectiveness (effective to use), efficiency (efficient to use), learnability (easy to learn), memorability (easy to remember how to use), safety (safe to use), and subjective satisfaction of an interactive product.

A product is effective in terms of how good it is at doing what it is supposed to do. It is efficient at supporting users in their tasks. A system or a product should be easy to learn, new users can begin effective interaction, once learnt retain the knowledge; this is important for systems or features that are used infrequently. A safe interactive system safeguards the user from precarious and undesirable situations.

With these usability goals and concepts in mind we can discern that the field of HCI as it relates to computer security is a vast one. To illustrate the field of usable security and privacy and its relevance not just for research or academia, I present a few examples and research of this fascinating field.

We start with CAPTCHAs. Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart is a mouthful and a good example of the intersection between security and usability.

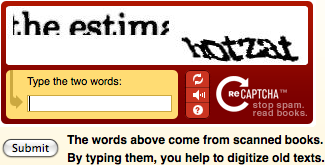

The security purpose of CAPTCHAs is to prevent bots from unauthorised access to websites or computing services. However, not that long ago, a CAPTCHA challenge would be the worst nightmare for visiting users: distorted words and numbers, letters and numbers that could be mutually confused (reading the number one ‘1’ as the letter ‘l’, font-dependent), blurred images, superimposed images, etc. Although the most popular CAPTCHA challenge is image recognition-based, some sites still use text-based challenges. The audio challenges were, and are, not necessarily any better.

A complex or difficult CAPTCHA challenge may ‘violate’ some of the usability goals described above. A poorly designed challenge might be easily defeated with OCR techniques, speech recognition, image recognition techniques, etc. It can also lead the user to undesirable conditions where the user is required to solve multiple challenges.

Fig 1. Old and experimental versions of text-based CAPTCHA challenges.

We move to Passwords. Over the years we have been given a myriad of advice regarding passwords. Research around passwords is more than abundant: mental models (on password creation, 2FA usage and users security habits), password policies (e.g. PCI-DSS: 90-day resets, expiration policies, composition rules), password-memorization techniques, software reinforcing strong password creation, password-strength metres, graphical passwords in general, graphical passwords for children, expert vs non-expert security practices on various areas (e.g. password handling/storage), security-related habits and behaviours of users, developers, administrators, security practitioners, and the list could continue.

These research examples can influence how policies are composed within organisations. A couple of evident ones: how often to force password resets and password composition rules. As we note below, research has been highlighting the negative impact of these two practices.

The last example is on cookie banners and disclaimers. This example is usable privacy rather than usable security, yet relevant to the post. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the ePrivacy Directive (ePD) have set regulations governing cookies on websites. Cookies are important artefacts giving businesses important insight information and behaviour of users visiting their websites. However, cookies can contain enough information to identify a user without their consent.

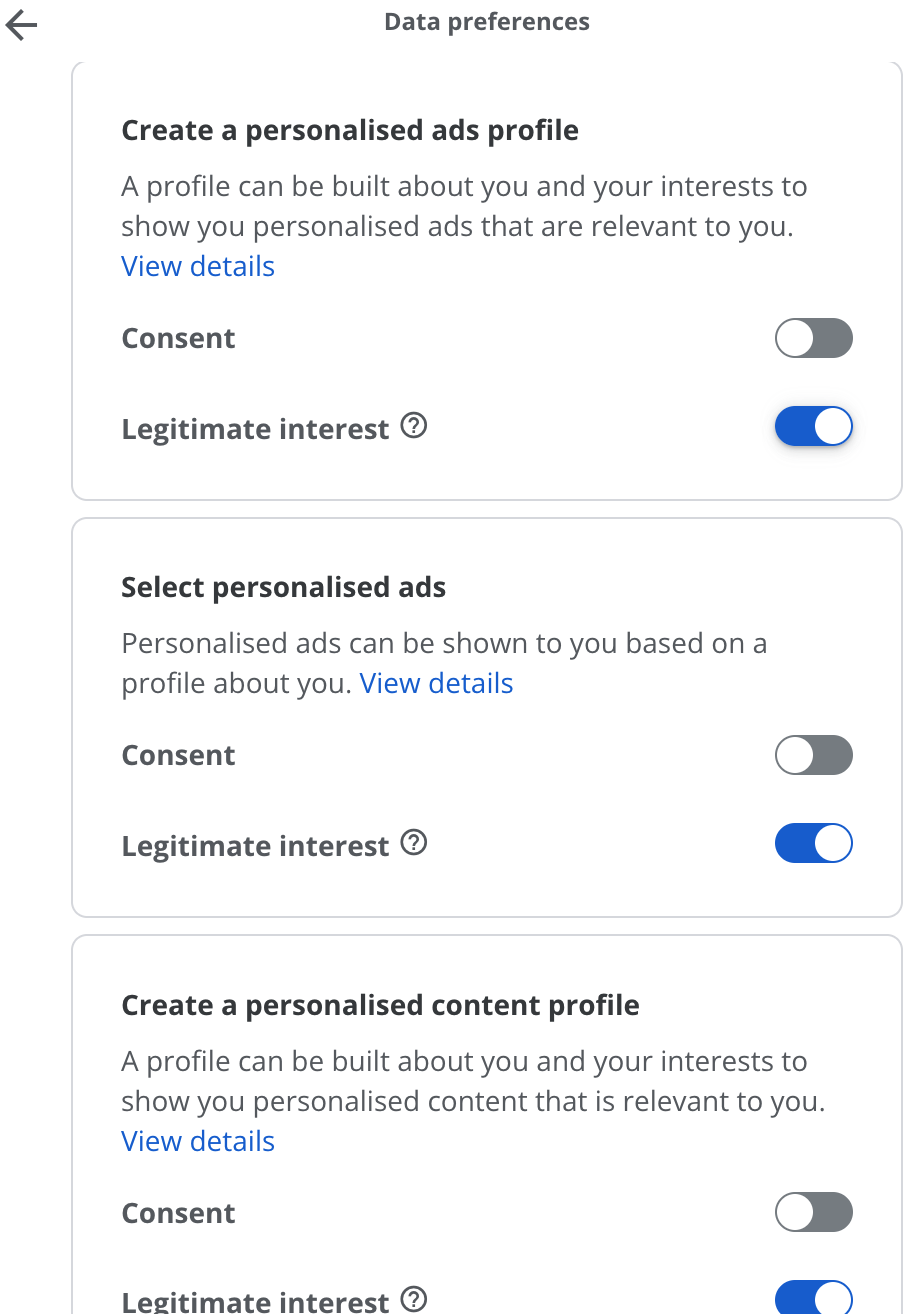

After the introduction of these stricter regulations many businesses and websites started adopting a practice known as “dark patterns” to increase the acceptance of all cookies from users. Dark patterns are practices of designs, vague and ambiguous language, positive or negative framing of the message, options enabled by default, etc. on cookie banners to nudge users towards giving consent, thus violating legal requirements set by ePD and GDPR.

Fig 2. Cookie banner example of a Dark Pattern.

How is Usable Security relevant for practitioners? #

Wrapping up, it is likely that the reader has come across these and multiple other examples of usable security and privacy without noticing the, often, subtle intersection between the human factor and the cybersecurity artefact, application, or coding practices.

As a cybersecurity practitioner, developer, sysadmin, or other role in cybersecurity you can keep in mind the usability goals mentioned at the top of this post and apply them to your tasks. For example, as a developer or designer, familiarise yourself and be a champion of Privacy by Design[1] to avoid creating dark patterns (in general, not just for cookie banners).

You could implement complementary solutions to CAPTCHAs to minimise user-interaction friction with challenges and have the challenge as the last gate. Choose a CAPTCHA which is adaptive to multiple devices, accessibility friendly, and it’s safe to use.

Keep in mind the usability principles when buying a third party security or privacy solution: is it safe to use? Does it reduce the chances of misconfigurations? Would users love/hate using the product? If users don’t like the product they are likely to avoid its use or may achieve maximal performance. Look into how easy it is to operate after some time away from the system.

For example, some Security Operations Centre (SOC) solutions have specific query languages to sift through logs. Are users of this SOC solution familiar with the particular query language? Is there help or examples available on the solution? How easy is it to recall the syntax if the user doesn’t run queries often? Once users have learnt how to use it, can they keep a high level of productivity?

Following years of research[2,3] and proof that password expiration policies do more harm than benefit the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) made long overdue recommendations for user password lifecycle:

“Verifiers SHOULD NOT impose other composition rules (e.g., requiring mixtures of different character types or prohibiting consecutively repeated characters) for memorized secrets. Verifiers SHOULD NOT require memorized secrets to be changed arbitrarily (e.g., periodically). However, verifiers SHALL force a change if there is evidence of compromise of the authenticator” [4]. Hence, if your role is sysadmin or policy maker you can follow guidelines and adjust password policies accordingly. On the other hand, there are regulations which may force periodical password expiration, e.g. PCI-DSS change of password every 90 days. However, these regulations have compensating controls which allow room for usable security improvements.

If I managed to pique your interest, I leave below a few groups focusing their research on human-centred, usability, privacy and computer security.

CHORUS Lab

https://chorus.scs.carleton.ca/publications/

LERSSE

https://lersse.ece.ubc.ca/

Behavioural Security Research Group

https://www.besec.uni-bonn.de/

CyLab

https://cylab.cmu.edu/research/usability.html

References: #

[1] Privacy by Design. Privacy Commissioner of Ontario Ann Cavoukian.

https://iapp.org/resources/article/privacy-by-design-the-7-foundational-principles/

[2] Quantifying the Security Advantage of Password Expiration Policies.

http://people.scs.carleton.ca/~paulv/papers/expiration-authorcopy.pdf

[3] Frequent Password Changes are the Enemy of Security.

https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2016/08/frequent-password-changes-are-the-enemy-of-security-ftc-technologist-says/

[4] NIST 800-63-3: Digital Identity Guidelines

https://pages.nist.gov/800-63-3/sp800-63b.html